The Dangers of Mislabeling Inflation: A Response

If you call everything inflation, you lose any explanatory, and hopefully predictive, power of your model of the economy.

If you follow my work, you know I think this is one of the biggest problems people face in understanding the financial system. They mislabel price increases as inflation instead of the very specific thing it is, an increase in the money supply. However, they often unequally apply the correct definition post hoc when they look backwards to find an explanation for current price increases. They see price increases, there must have been money printing. Instead of thinking of money supply as the first principle and prices as a separate complex phenomena sometimes related, they start with prices as the first principle and scour recent history looking for things to call money printing or assume money printing had to have occurred.

For example, let's say government debt increased over a decade-long period and prices did not go up, perhaps even slightly fell over that time. Then a huge flood ravages half the country and prices skyrocket by 25%. Since every price increase is mislabeled as inflation, when they reverse engineer the situation to find money printing, they will find that government debt has ballooned, and voilà inflation. But when prices inevitably crash on the other side of the transitory disruption, people will be left stupefied.

It is of utmost importance to any explanatory, and hopefully predictive, model of the economy that we correctly label inflation.

Inflation vs Deflation

I recently read a post by Jesse Myers, Deflation vs. Inflation, where he debunks Peter Zeihan's comments about bitcoin on Joe Rogan. Many of us did the same. I totally agree that Peter is pompously wrong on this, and I think Jesse did a good job explaining the big points. However, I think we can learn something by pulling a few strings present even in Jesse's writing, where he mislabels inflation as deflation.

The first part of the post is good. He points out that Peter misuses the term, "monetary inflation" where he meant deflation. But, the devil is in the details. Peter didn't mean deflation as properly defined either, even Peter knows Bitcoin's supply is fixed. He meant something along the lines of 'a regime of rapidly falling prices'. Jesse misinterprets this IMO into gently falling prices, then proceeds to call falling prices deflation.

Jesse quickly introduces the adjectives "inflationary" and "deflationary" to take the place of nouns inflation and deflation, breaking the link to money supply and replacing with a link to prices.

However, people who study currencies use these terms to denote the inverse measurement: how the price of goods track over time relative to that currency. An “inflationary” currency means that you have to spend more units of currency to buy the same thing over time (have you ever compared a menu of prices in dollars from the 1970s vs. today?). Conversely, a “deflationary” currency regime is when prices deflate over time and each unit of currency buys you more, not less.

"An inflationary currency" just describes a currency whose supply expands with time, not prices, as we'll see below. Jesse says, "you have to spend more units of currency to buy the same thing over time," but what about diminishing marginal returns or natural shortages? If lumber costs $1/linear foot in 1950, and then after all the local forests are used up it has to be imported at $2/linear foot in 1970, does that mean the currency was "inflationary"?

An inflationary economic environment is one that naturally favors an increase in the supply of money, where business is booming, and the economy is expanding and is demanding more credit. However, most people think only in terms of prices->inflation. That's a mistake, because it sends you down the road of reverse engineering and mislabeling other things.

The Gold Standard was Inflationary

Jesse goes back in time to find a period of falling prices, because he claims falling prices are due to a "deflationary currency". The period he uses is the 150 years in the US from the Revolution to the Federal Reserve. This period was characterized by gently falling prices (for the most part) but was not deflationary.

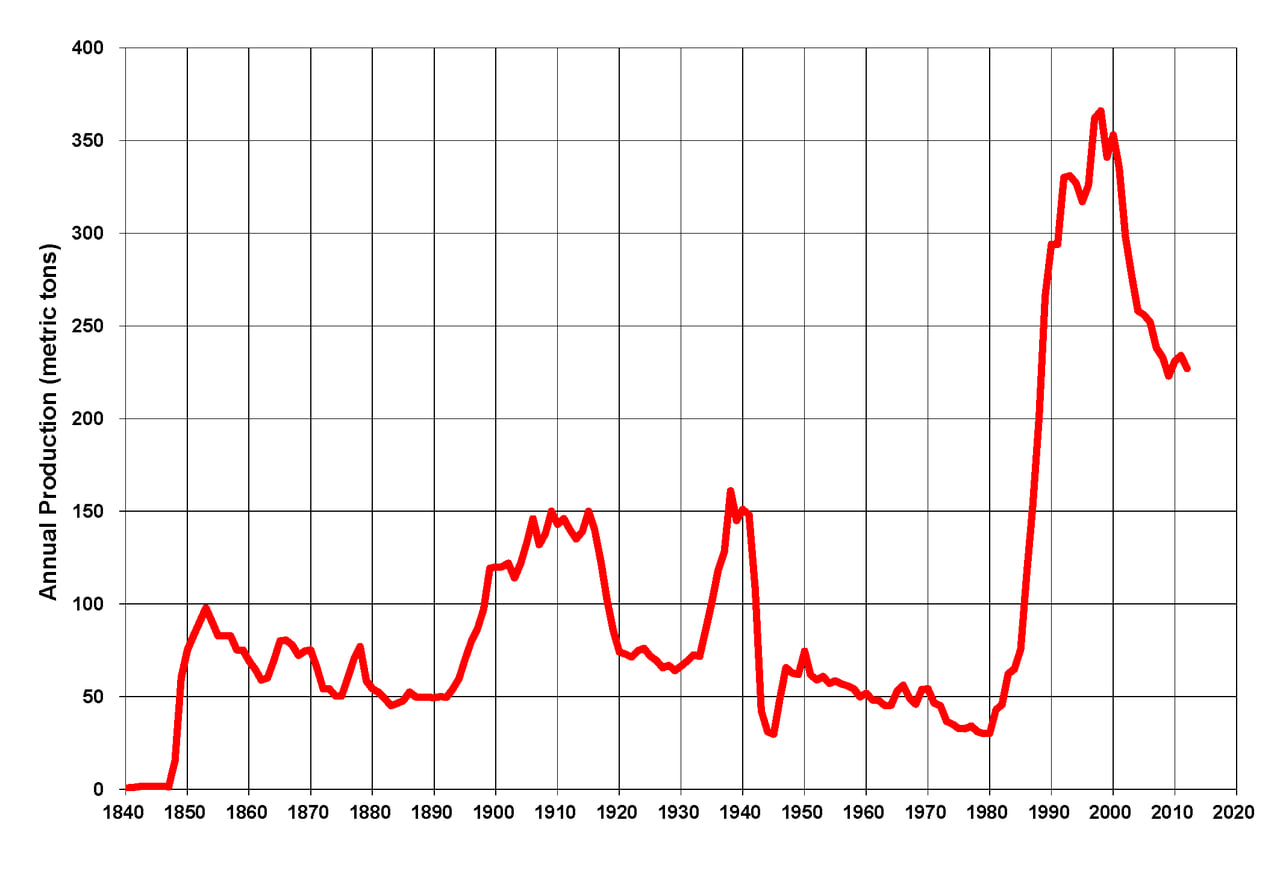

Gold mining started in the US in 1804 in North Carolina, and went through many gold rushes. The currency itself went through several legal devaluations. The Coinage Acts of 1834 and 1873, the latter also demonetized silver, effectively slashing the money supply, which fits with Jesse's theory, but was a political event and not a property of gold.

The most famous gold rush was in California around the year 1849, smack dab in the middle of this timeframe and the Industrial Revolution. American gold production increased 70x and global production 4x in less than 5 years. And that is just one gold rush during this long period.

My point here is not to claim the gold standard is as inflation prone ("inflationary") as the current system, it is to say that the gold standard was not a period of deflation. Prices gently falling was not due to "deflationary" money. All we can say about this period is that prices gently fell DESPITE inflation. See the twisted place you can get to if falling prices must be due to deflation?

The Industrial Revolution that Jesse beautifully describes in his post, was an inflationary environment. Debt was productive, new industries created, productivity spiked, and not only did the supply of gold increase but credit first started to increase and become commonplace. Gold acted as a useful brake on inflation during this period due to its lower elasticity. It resists credit expansion, but is not immune. The reason prices gently fell is because of the high growth environment exceeded the natural brakes of gold, not because of deflation or a deflationary currency.

Identifying Deflation with Prices

The whole argument is premised on prices being used to identify deflation or inflation, and masks any insight we might be able to glean from first-principle evaluation. The question is not whether a currency (prior to bitcoin) is inflationary or deflationary, they were all inflationary, but how elastic is the inflation?

A gold standard had a low and steady elasticity. The current credit-based system has high and variable elasticity. This insight is wholly separate from prices. Bring prices into the argument and you can mistake low inflation, low elasticity for outright deflation, and then claim deflation is good.

Gently falling prices are good. Deflation is not good. Actual deflation, shrinking of the money supply, does not result in gently falling prices. It results in rapidly falling prices. That is the point Peter Zeihan was trying to make. Where he gets it wrong is, not in misjudging the ills of deflation, but that bitcoin's price appreciation is a permanent property and is due to deflation. He admits to thinking it's a permanent property when he clumsily says it won't be adopted because the price keeps going up.

This is another example of merging prices with inflation/deflation. Zeihan identifies deflation with rapidly falling prices (perhaps more correctly than Jesse does with gently falling prices), deflation is not good, and since things priced in bitcoin are rapidly falling, Peter's logic concludes that bitcoin is not good. See how the merging of price with money supply leads us down the road of mislabeling everything else? Bitcoin's rapid appreciation is a property of its adoption phase, it is not deflation, it is pure appreciation. Once widely adopted its rate of appreciation will slow drastically to sustainable levels, but that slight appreciation of <5%/yr (like gold in the 150 years of Jesse's example) won't be deflation either.

The question of how much bitcoin will appreciate in the post-global-adoption world will rest on how elastic bitcoin will prove to be with no underlying inflation. I think it can be roughly that of gold. Gold is inflationary at the base layer, as we discussed, and less elastic in terms of circulation credit, because high storage and settlement costs limit velocity and credit employment. Bitcoin is not inflationary at the base layer but will likely be slightly more elastic in circulation credit because of its ease of settlement, programmability and employment.

Thanks for reading. To get early access to future posts, please consider becoming a paid member!