Testing the Money Printing Hypothesis

Exploring three hypotheses about money printing, QE, and the flow of funds in the modern financial system.

I cannot provide this important Bitcoin and Macro analysis without you.

Please consider supporting independent content!

Intro

We've been having a discussion on Telegram about the nature of reserves held at the Federal Reserve by depository institutions. There is a disagreement on whether or not QE, and its associated creation of reserves used to swap for securities, constitutes money printing. My position is that it doesn't, while a few others take the opposite view.

In this post, I’ll lay out some charts and arguments to build on that discussion. My goal is to learn, adjust my view if necessary, and get closer to the truth. I'm open to correction and will update this post as needed. Let’s figure this out together.

Methodological Note:

In this post, I’ll take a scientific approach: propose a hypothesis, devise a test, and evaluate whether the evidence supports or refutes the hypothesis. I recognize this method contrasts with the Austrian school’s praxeological approach, which relies on deductive logic from first principles rather than empirical testing.

My aim isn’t to challenge Austrian methodology itself when well-founded, but when its application universally fails in real-world predictive power we have to examine our priors. There are three things to look out for:

- The logic is flawed (I don't believe is the case generally true for praxeology).

- A premise is incorrect—often due to assumptions like ceteris paribus. If that premise always prevents predictions from materializing, one must question those assumptions.

- A variable is misidentified—such as using M2 as a proxy for money supply, which is counting the wrong thing.

Hypothesis #1: Reserves created in QE leak out into the economy, specifically via Vault Cash

Vault cash is the physical currency (bills and coins) that banks keep on hand in branches and ATMs to meet customer withdrawal demands.

Vault cash operations involve banks requesting physical currency from the Federal Reserve, which delivers the cash and debits the bank’s reserve account by an equal amount.

As argued on Telegram:

"The $100 note you withdraw from Chase to buy a sandwich, comes from reserves/Fed balance sheet. Chase can create deposits in lending, but not notes. So when you withdraw it, ultimately Chase must source it from the Fed and they pay for it with the only currency the Fed uses — the reserves."

The hypothesis here is not that reserves are turned into vault cash—that is exactly how it happens. Instead, the claim is that reserves created in QE leak into the economy. The underlying question is whether QE is money printing, but the vault cash transformation used reserves long before QE. It's also not enough to say currency in circulation (CIC) increased in the QE regime, because CIC has increased every year except one (2000) since 1950. The claim is specific: that QE causes reserves to leak into physical notes.

To get a precise measure of how much money was transformed in this way, the formula is the change in CIC minus the increase in vault cash for a given year. When we run those numbers, we get a total of $1.46T in new money entering circulation since 2008 and the beginning of QE. The total amount of QE was $9T. Therefore, at most this mechanism would account for only 11% of that total increase in reserves.

But did it?

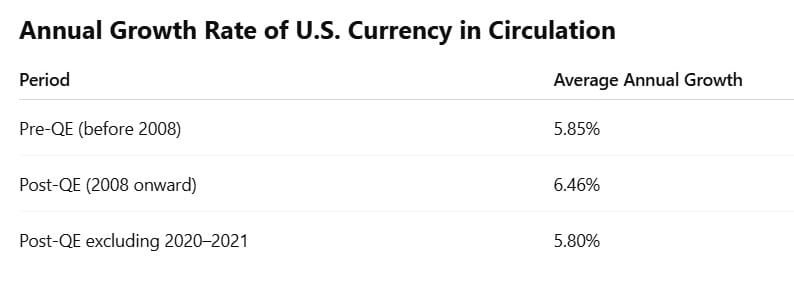

We've established that CIC increases every year. For QE to be the cause of that increase, we must show a change in the rate of CIC growth during the QE era. For the 10 years prior to 2008 and the start of QE, CIC increased at an average rate of 5.85% per annum. Since QE began, it has increased by 6.46% annually. That is slightly more, but not proportional to the rise in reserves from QE. Also, if we exclude 2020 and 2021—two extremely exceptional years in many hard-to-understand ways—the average post-QE CIC growth is 5.80% annually, slightly lower than pre-QE.

QE did not systematically increase the rate of physical money issuance, as the growth rate of CIC remained essentially unchanged.

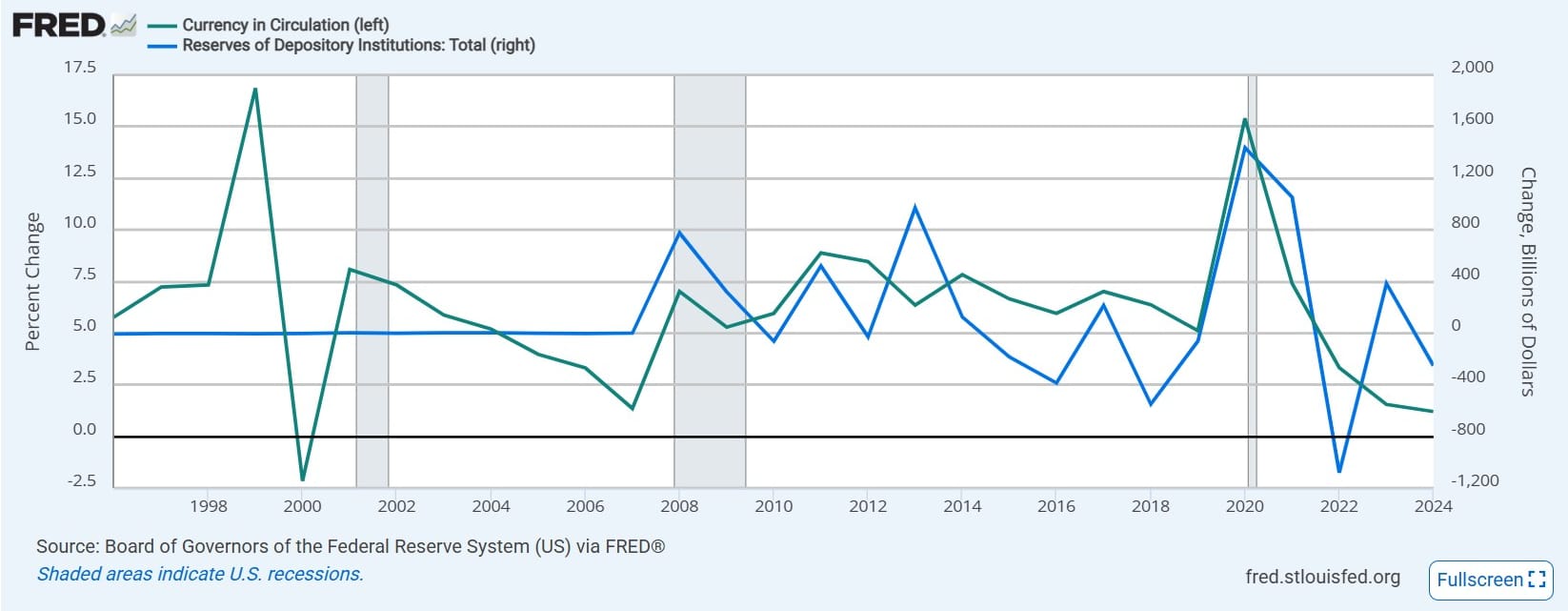

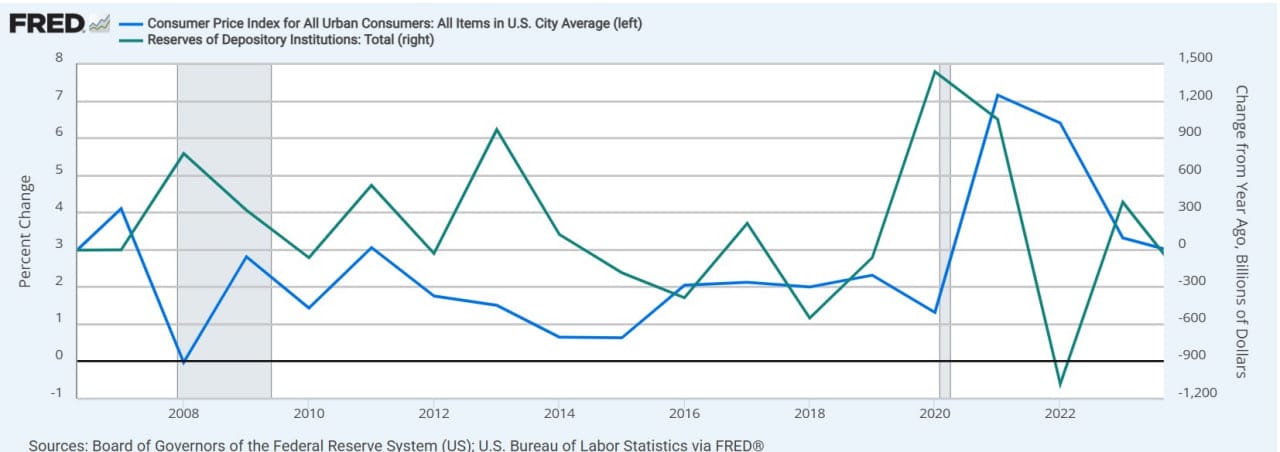

We can look at it another way—through correlations in annual changes. If increases in reserves cause increases in CIC, we should see a strong correlation. Below is a chart of CIC and reserves held by depository institutions at the Fed. The correlation since 2008 is +0.58.

While positive, this is only moderate—far from proving that QE reserves leaked out into the economy. More likely, CIC's consistent growth merely overlaps with QE-era reserve growth. Excluding 2020 and 2021, the correlation weakens further to +0.31.

The chart above is based on percent change, so I also tested absolute dollar changes in CIC. The correlation there fell to +0.4. Excluding 2020 and 2021, it turned negative: -0.18.

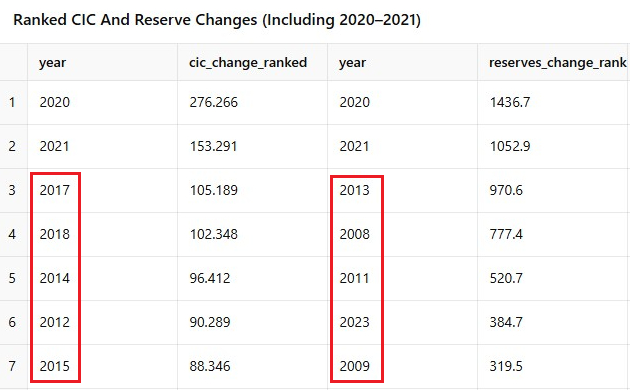

It is hard to pin down a correlation here, for the reasons stated above. So I tested a third approach: comparing the ranked order of annual changes. If there were a causal relationship, we’d expect some alignment.

What we find is the following: yes, 2020 and 2021 match up, but we've already identified those as exceptional. We shouldn't base our conclusion on two anomalous years while ignoring the rest. Excluding 2020 and 2021, the next five largest years of change show zero overlap—none of the top five reserve years appear among the top five CIC years.

Review

1) We've shown that the rate of change in CIC did not materially change from pre- to post-QE.

2) We've shown that there is no strong or consistent mathematical correlation between changes in reserves held at the Fed and changes in CIC. When 2020 and 2021 are excluded, the correlation disappears and turns weakly negative.

3) There is no consistent overlap between years with large increases in reserves and years with large increases in CIC, except for 2020 and 2021.

Conclusion

We have conclusively shown that reserves do not leak out into the economy via vault cash.

Hypothesis #2: Changes in the level of reserves directly impact price level

If this hypothesis is true, CPI and the level of reserves should show a strong positive correlation. Some claim there is both empirical and theoretical support for this.

But when we compare annual YoY CPI (all items) with the change in reserves held at the Federal Reserve, the correlation is −0.14. We could stop there—this is directly contradictory evidence. The hypothesis has no leg to stand on.

It might be argued that prices respond with a lag. So we shift CPI back one year. The correlation turns positive, but only weakly, at +0.40—still inconclusive.

More importantly, excluding 2020 and 2021—the most exceptional years—we find the correlation without a lag is −0.59, and with the one-year lag, −0.29. This is damning. The data appears to support the opposite view: that increases in reserves correlate with disinflationary years, not price increases.

This preliminary empirical evidence is in direct contradiction to the hypothesis–rising reserves do not lead to rising prices. In fact, it offers support for the reverse hypothesis, one I would support: reserves tend to rise in disinflationary environments.

Hypothesis #3: Money to buy Treasury debt comes from the Federal Reserve

This is a persistent belief. Many argue that the Fed is monetizing the debt—that the whole process is just a thinly veiled direct monetization, using primary dealers as a cosmetic middle layer.

But that’s precisely the point—the distinction that makes it not monetization. Primary dealers must already have dollars to buy Treasuries from the government in the first place. What would a primary dealer do if they bought an issuance of 10-year Treasuries, but the Fed only planned to buy 2-year and shorter maturities for the next few months?

Where do those dollars come from? Not from the Fed at the moment of issuance. The vast majority of funds used to participate in Treasury auctions come from repo and internal bank liquidity, and only theoretically from loans of newly printed money.

QE Flow

- Primary dealer obtains funding — typically through repo markets or internal liquidity, using existing money (not newly created loan deposits).

- Dealer purchases Treasuries at auction — pays with funds from step 1; the Treasury goes on the dealer’s balance sheet as an asset.

- Federal Reserve conducts QE — buys the Treasury from the dealer and credits reserves to the dealer’s affiliated depository institution (which holds a Fed account).

- Depository institution credits the dealer’s account with an equal deposit.

- Dealer repays original funding — uses the deposit from step 4 to repay the repo lender or other cash provider from step 1.

- Government makes interest and principal payments on the debt to the Federal Reserve.

Net Effect:

- Existing money moved from the repo market into the Treasury General Account (TGA).

- The dealer is flat: sold the asset, repaid the funding.

- The banking system holds more reserves, but these are non-fungible, non-circulating, and therefore not money in any meaningful sense. Without QE (steps 3 and 4),the flow still works: the process would end with the dealer paying off its lender as the Treasury services the debt over time.

No new money was created, unless the initial Treasury purchase was funded by a loan that created a deposit, which is highly unlikely, because it means the repo market was frozen.

For this to be true monetization, we would first have to prove that reserves created in QE are actual money. While they are counted in M0 (the monetary base), that classification is arbitrary and misleading. Reserves don’t circulate. They can’t be spent by the public or businesses. They exist only within the banking system and serve a regulatory or settlement function.

There is no circular loop where the Fed gives money to banks so they can buy Treasuries, which are then sold back to the Fed. That narrative misunderstands both the timing and the accounting.

The Fed does not fund government spending. It swaps reserves for existing securities on the secondary market that do not enter the public sphere. There is no direct monetization, and QE is not a roundabout version of it. It is a delayed asset swap, not a fiscal subsidy.

Your support is crucial in helping us grow and spread my unique message. Please consider donating via Strike or Cash App or becoming a member today and get more critical insights!

Follow me on X @AnselLindner.

I cannot provide this important Bitcoin and Macro analysis without you.

Bitcoin & Markets is enabled by readers like you!

Hold strong and have a great day,

Ansel

- Were you forwarded this post? You can subscribe here.

- Please SHARE with others who might like it!

- Join our Telegram community

- Also available on Substack.

Disclaimer: The content of Bitcoin & Markets shall not be construed as tax, legal or financial advice. Do you own research.