On the Origins of Money and the Monetary Chasm

How Society Shaped the Origins of Money

I cannot provide this important Bitcoin and Macro analysis without you.

Please consider supporting independent content!

Introduction

A recent blog post by Jesse Myers on Once-In-A-Species has sparked fresh thoughts for me on the deep origins of money. While I’ve written extensively about the recent and medium-term future evolution of money, this offers an opportunity to apply some of those same principles to the distant past.

Jesse presents a compelling and interdisciplinary theory: that a recently discovered genetic mutation between 300,000 and 160,000 years ago heightened our symbolic reasoning and aesthetic instincts, and led to a fascination with collectibles like shell beads. He argues this shift enabled the emergence of money, which then allowed human society to scale in size and complexity. In his view, money was the catalyst that enabled modern humans to outcompete earlier hominins.

"Humanity’s triumph is likely due to a single amino acid mutation between 300,000 - 160,000 BP supercharging our brain centers for abstract thought, allowing for the critical mass of interest necessary to develop the concept of money, and leading to our overpowering competitive advantage of multi-tribe population coordination unbounded by Dunbar’s number."

Szabo to Myers

Nick Szabo's 2002 article, Shelling Out: The Origins of Money remains perhaps the most pivotal work on the deep roots of money. In it, he argues that money originated as an evolutionary tool for managing trust and reciprocity in early human societies. Long before states or markets, scarce and costly collectibles served as proto-money, enabling cooperation and reputation-building beyond immediate kin. Money, in this view, emerged from the social pressures of increasingly complex group life.

Jesse Myers’ contribution adds genetics to the conversation, especially the potential role of the hTKTL1 mutation as the starting point for humans’ unique appreciation of collectibles. He further proposes that money was the primary catalyst that gave modern humans an edge over earlier hominins, effectively bootstrapping the scaling of human societies—and perhaps even defining what makes us human.

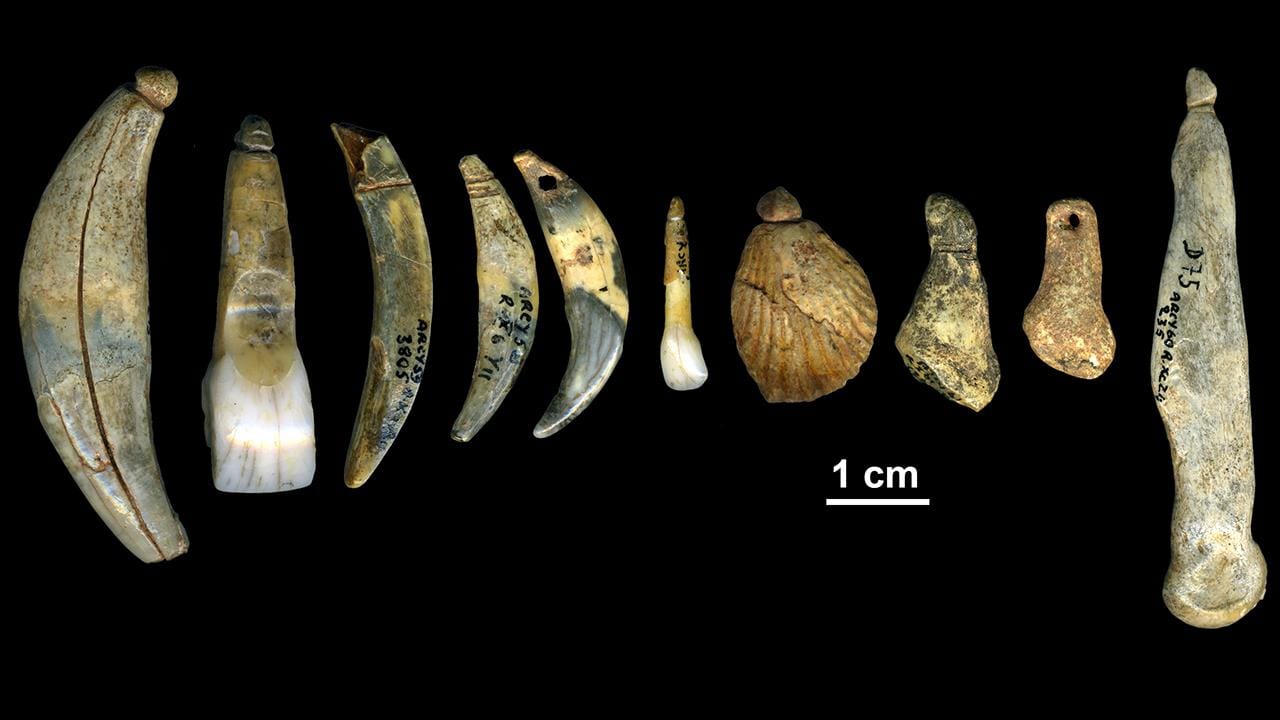

It’s true that many gene mutations occurred during the early development of Homo sapiens sapiens, with hTKTL1 appearing to be the most recent of the major cognitive-enhancing changes. However, while bead jewelry has been found as early as ~142,000 BP, symbolic artifacts remain extremely rare before ~70,000 BP. The vast majority of archaeological sites from that period or earlier show no symbolic artifacts at all.

To quantify this rarity, I used ChatGPT to estimate the number of known archaeological sites dating to ~70,000 BP or earlier, and those containing symbolic artifacts. The result: between 1,000 and 1,500 sites globally, with only 10–15 showing any symbolic artifacts of any kind, and just 7 sites containing shell beads. In other words, fewer than 1.5% of early sites display symbolic behavior. While additional discoveries may raise those numbers modestly, it is highly improbable that such behavior will ever be shown to have been widespread or common before ~70,000 BP.

For comparison, of the ~300 known Neanderthal sites globally, 5–8 contain symbolic artifacts — yielding a slightly higher symbolic rate (1.7–2.7%) than that of early modern humans prior to 70,000 BP. That’s an important point, because after 70,000 BP—and especially after 50,000 BP—we begin to see a significant rise in symbolic behavior at modern human sites.

Genetics

The timeline above raises a crucial question: if the hTKTL1 mutation occurred well before 70,000 BP, why didn’t symbolic behavior begin outpacing that of other hominins until over 100,000+ years later? To answer that, we need to consider not only genetics, but also the roles of language and broader social evolution—especially around the pivotal 50,000 BP mark.

Myers argues that a mutation in the hTKTL1 gene increased our affinity for collectibles, and that this shift enabled humans to use goods in a monetary way. In his view, money was the key innovation that unlocked larger social structures and more complex human organization.

"...but where this [gene mutation] seems to have really mattered was with respect to having the capacity to appreciate and value scarce commodities... This over-developed brain wiring supercharged our interest in scarce assets and our drive to obtain them."

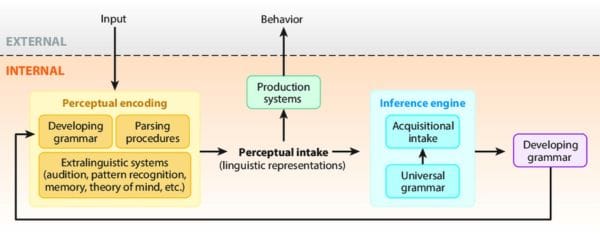

While it’s likely the mutation heightened our appreciation for symbolic or rare objects, it doesn’t follow that this alone caused proto-money to become a medium of exchange. The hTKTL1 mutation seems to have enhanced neurogenesis in the frontal cortex more broadly, strengthening abilities related to language, planning, memory, and social coordination. In other words, it provided a cognitive package–the raw material needed to scale up social life into larger, more interconnected, and more cooperative groups.

In the archaeological record, symbolic artifacts begin to appear more frequently after 50,000 BP and become widespread by 40,000 BP. A relatively rapid rise 100,000+ years after the hTKTL1 mutation. This timeline also coincides with what many experts consider the emergence of fully structured language. The development of complex language likely played a central role in expanding symbolic behavior, enabling cultural transmission across generations, and facilitating the transition from collectibles to functional mediums of exchange. This marks the crossing of what I call the monetary chasm, where abstract value became widely recognized and socially embedded in exchange systems.

Collectibles To Money

Not all modern human populations exhibited intense symbolic behavior or developed store-of-value practices. Even today, several hunter-gatherer populations have not progressed to the widespread use of store-of-value goods, let alone medium of exchange. This suggests that the emergence of proto-monetary behavior was not a universal human instinct, but a cultural adaptation that only occurred under certain conditions.

If the use of shell beads or symbolic collectibles were purely the product of a shared genetic mutation—as Jesse Myers’ theory would predict—then we would expect this behavior to appear evenly across early modern human populations. But that’s not what we find. Shell beads, pigment use, and other symbolic artifacts appear in only a small fraction of sites prior to 70,000 BP and seem to have arisen in specific regions around 50,000 BP before diffusing more widely.

Geography clearly played a massive role. Regions with abundant trade routes, environmental variability, and access to resources likely experienced higher population densities and more frequent social interaction. These pressures would have created coordination challenges, which in turn fostered the need for shared social tools like symbolic language, reputational signaling, and eventually money. In contrast, groups in more ecologically stable or isolated areas may never have faced those pressures and therefore had little reason to develop or adopt symbolic or monetary systems.

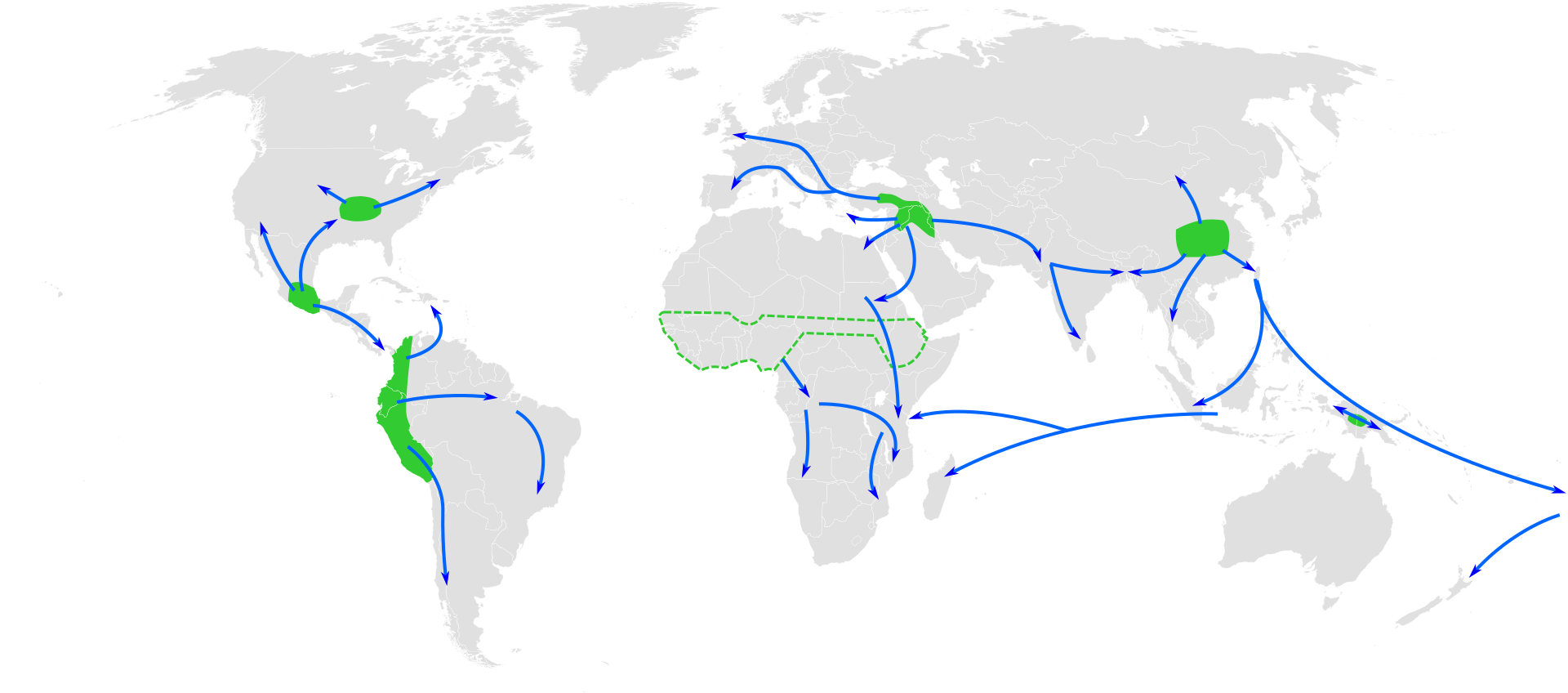

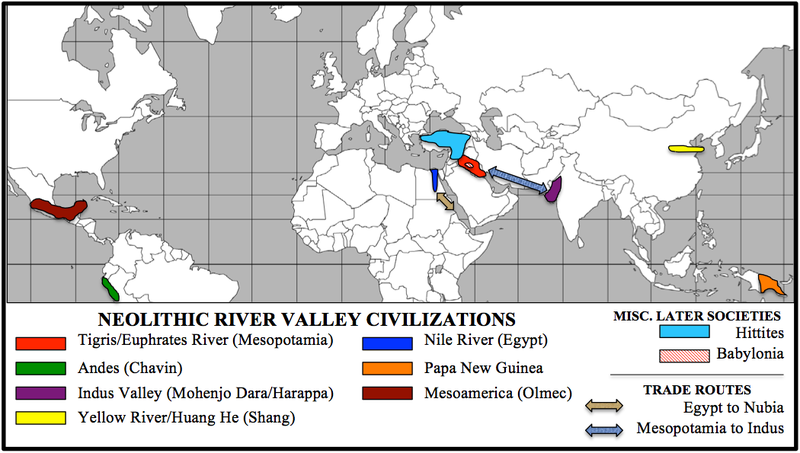

We can tentatively identify two major waves of symbolic and monetary advancement. The first occurred around 50,000 BP, coinciding with demographic expansion and the spread of symbolic artifacts like beads and engravings. The second came at the end of the Upper Paleolithic, between 14,000 and 12,000 BP, with the rise of agriculture in high-density hubs such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, China, and Mesoamerica. These regions appear to have developed monetary systems independently, rooted in their own material cultures and economic structures. Elsewhere, the concept of money spread primarily through diffusion, not reinvention.

If Myers’ theory is correct—that a universal genetic mutation gave humans an innate propensity for money—then money and civilization should have emerged far more evenly across the globe. The fact that they did not, and that monetization followed distinct geographic and economic patterns, points strongly toward environmental and organizational factors as the primary drivers.

The Monetary Chasm

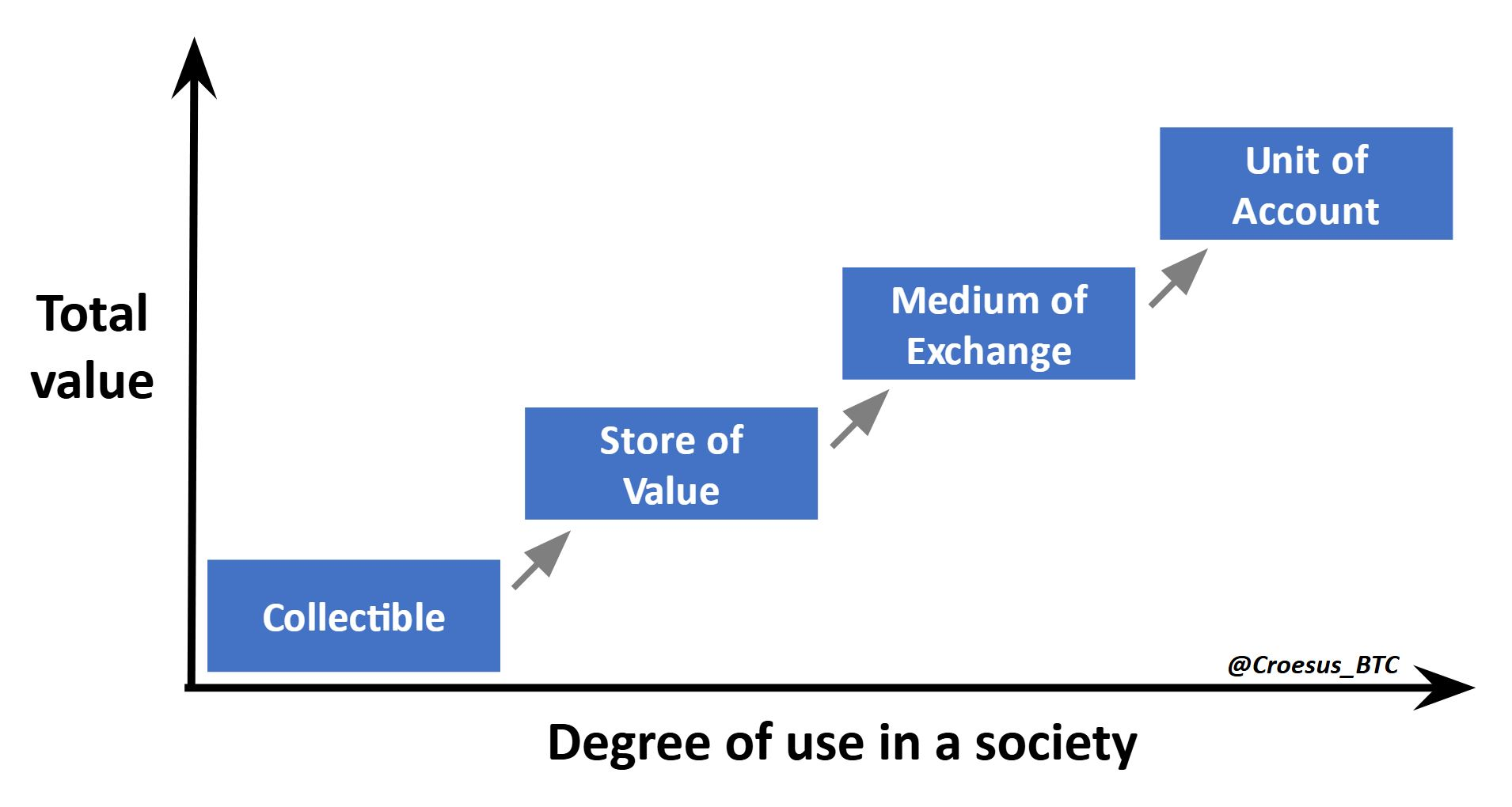

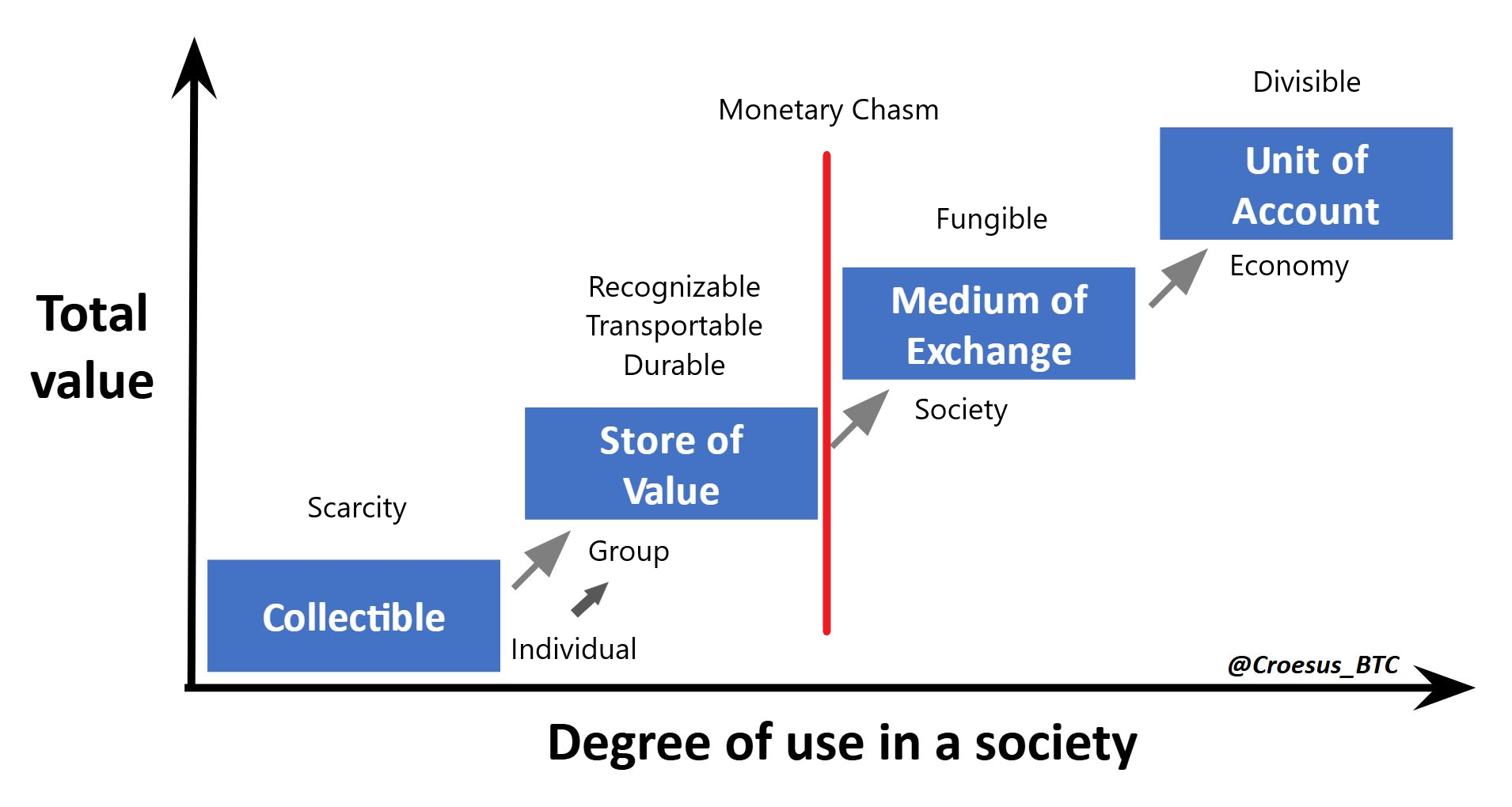

Each stage in the monetization process adds a new monetary function and is characterized by the emergence of different traits. Collectibles are typically valued for scarcity and symbolic weight. Store-of-value goods require additional characteristics: durability, recognizability, and portability. This is also where value begins to shift from purely personal preference to intersubjective consensus, meaning its usefulness depends on the shared beliefs of a group rather than just individual desire.

The key transformation happens at what I call the “monetary chasm,” the leap from a simple store of value to a true medium of exchange. Modern humans were not alone in reaching the store-of-value stage. Neanderthals and Denisovans likely had store-of-value goods long before modern humans did, like weapons, jewelry, hides, or engravings. But what set Homo sapiens sapiens apart was the coordination problems brought by scaling society.

This was no small step. Crossing the monetary chasm required a major leap in social cognition. It required the ability to plan beyond immediate needs, to defer consumption, and to believe in the stability of a collective consensus. It was a shift from simple swaps—"I want what you have, you want what I have"—to abstract exchange: "I will accept something I do not need now, because I trust it will be useful later." Crossing the chasm began as a profound social revolution that led to an economic revolution.

Fungibility becomes important when crossing the chasm, because if not uniform each item would have a barter-like quality, and it is important for mental calculation. Fungibility is so pivotal to medium of exchange goods, and so rare in collectibles or stores of value, wherever it is found we should at least consider the possibility the good in question was some sort of primitive attempt at crossing the chasm.

Direction of Monetary Evolution

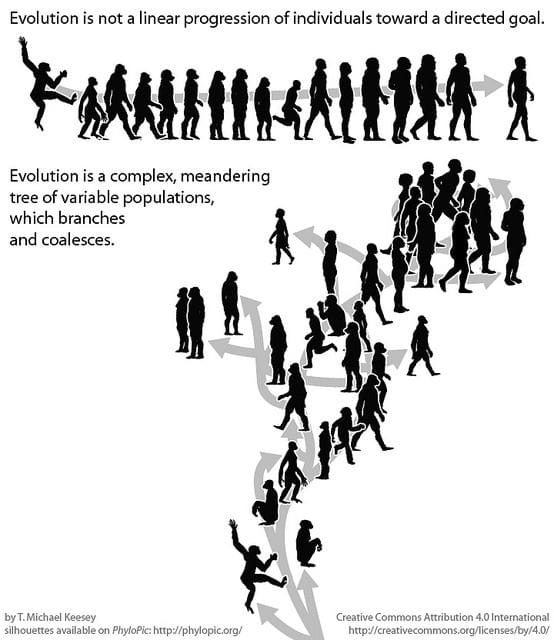

My core thesis of monetary evolution is that money evolves in response to cultural development and economic structure, which itself is driven by geography and demographics. We can apply this across the spectrum, from the deep origins of money to our current shift from credit-based systems back to commodity money like Bitcoin.

Many goods can possess monetary characteristics, but there is typically a dominant economic medium that best serves the structure and demands of its time.

In periods of expansion, with high integration and trust, more elastic forms of money are preferred by the market because credit enables faster growth and innovation. In times of decline, with fragmenting integration and low trust, commodity money tends to be preferred due to its lack of third-party dependence.

Myers hints at an evolutionary framing, too, but it is quite different:

"The history of money in human civilization is characterized by an ongoing process of upgrading from one form of money to a fitter, more scarce form of money."

This is an extremely popular view in Bitcoin circles—that monetary history is a steady refinement toward scarcity. However, this idea is clearly incorrect. Let me explain.

Silver and gold coins have been minted for the last 2,500 years, with gold being the more scarce of the two. One would expect a gold standard to be the rule, but the predominant medium of exchange and unit of account has flipped multiple times throughout history.

First, it was silver with the Greek drachma and Roman denarius (4.3 and 4.5 g respectively), minted from Spain to India. The denarius had been so debased by 312 AD that Emperor Constantine minted the gold solidus (4.5 g of gold). Gold remained the dominant unit of account in the East, but in the West the Frankish silver denier was introduced in 755, where it reigned supreme. Around 1250 the solidus had failed and the Italian gold florin and ducat (3.5 g gold) took prominence in the Mediterranean and Europe (along with the gold dinar). After the Late Medieval Depression silver was discovered in the German mountains and the silver standard came back with the mark and Spanish real. The real then served as the global medium of exchange until the British moved to gold in 1816 (the Dutch used reals in their trading empire). China never adopted gold or silver standards at all until the 19th Century, remaining with copper or bronze for most of this time.

As you can see, monetary history is not a straight line from copper to silver to gold. Recency bias from the Classical Gold Standard likely plays a huge role in this confusion. In reality, the Classical Gold Standard was relatively short-lived—lasting from 1816 to 1971 at the extremes, but more narrowly from 1871 to 1914—and was quickly replaced by a new monetary evolution. When we entered the ultra-high-trust, integrated era of the post-WWII Western order, a super-elastic, credit-based U.S. dollar evolved in the shadow banking system to what we have today.

*Note: I wrote a post posing the challenge to those with inflation-centric arguments to explain why bitcoin will win if gold failed. The answer lies in understanding the cycles in the international order and the subsequent effect on the choice of monetary tools:

"Evolutionary Monetary Theory (EMT) provides a consistent lens through which to view gold's failure and bitcoin’s success. The market chooses money based on the specific circumstances of the time. In a peaceful, high-trust, low-debt environment, people gravitated toward credit-based money. However, as those conditions inevitably change, people will naturally gravitate toward a money that optimizes their situation under new circumstances."

That is not to say that scarcity never matters, it does under certain circumstances when society returns to a commodity money standard. In this transition, Bitcoin is the logical choice over gold. It is superior in nearly every aspect, except in extreme scenarios that are unlikely to unfold in the foreseeable future—such as a return to a preindustrial dark age. But that is a discussion for another post.

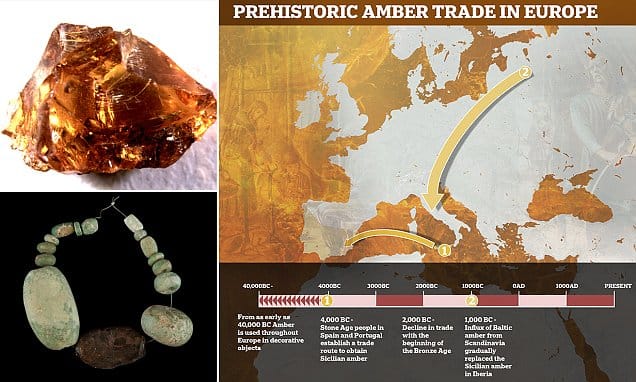

Before Gold and Silver Coins

To accentuate this point of the medium of exchange not following the refinement to scarcity, if we back up further, gold and silver had been known and valued for millennia before their appearance as coinage around 650 BC in the Aegean. Despite thousands of years as the scarcest goods, they had not become widespread mediums of exchange. Instead, shells, beads, salt, livestock—all much less scarce—served as money across many societies.

Less scarce metal objects of different types were also used as money prior to gold and silver. A study conducted by archaeologists from the universities of Göttingen and Salento and published in the Journal of Nature Human Behaviour in 2024, analyzed over 20,000 metal objects from more than 1,000 sites across Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, and Germany, dating between approximately 2300 BC and 800 BC. The researchers found that by around 1500 BC, these metal items were likely intentionally fragmented into pieces weighing roughly 10 grams, a consistent unit across Europe. This uniformity suggests that these fragments were used as a form of money, predating the creation of coins by centralized states.

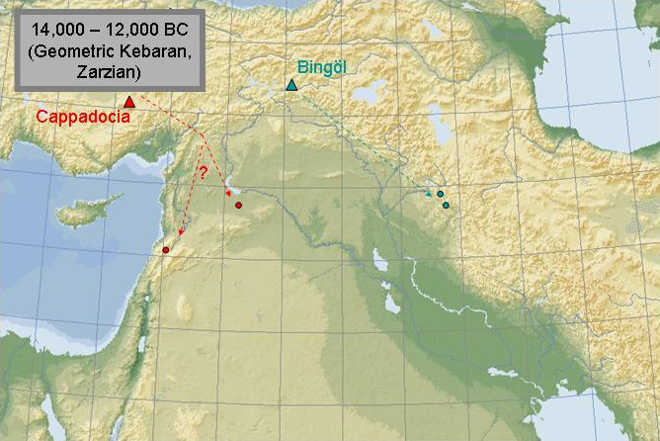

There is also evidence of uniform obsidian blade "factories" or workshops throughout Europe and the Near East. Most obsidian production and trade sites date to the Neolithic period, around 14,000 to 6,000 BP, associated with early farming and large-scale trade networks. But the earliest known obsidian blade production site is at Melka Kunture in Ethiopia, dating back to a mind-bending 1.2 million years ago, and throwing a wrench in monetary discussions. Uniformity in blade production, in other words fungibility, is a characteristic of crossing the monetary chasm.

Where Scarcity Does Matter

Throughout history, money has not followed a linear path toward scarcity. Applied to the deep origins of money, this presents a strong case against the idea that scarcity or symbolism necessarily leads to the emergence of money. Money is a social tool that evolves to serve specific economic needs. Its “fitness,” in the evolutionary sense, is ultimately defined by the structure of society—not by its inherent scarcity.

But that is not to say scarcity never matters. It doesn't matter as much during the periods of general expansion, because elasticity can enable higher levels of quality growth. But when the global environment is toward decline, scarcity really matters. When you are looking for places to preserve purchasing power in a collapse, the harder money tends to win.

Conclusion: Society Gave New Meaning to Collectibles

Jesse Myers presents a bold theory: that a genetic mutation (hTKTL1) enhanced our appreciation of collectibles, which then led directly to the invention of money and the scaling of human society. In his view, the sequence runs mutation → money → social complexity, and this is what allowed modern humans to outcompete other hominins.

But the archaeological and historical record tells a different story. Collectibles and symbolic artifacts were exceedingly rare prior to 70,000 BP and only became widespread after 50,000 BP, suggesting that social and environmental factors at that time—not a universal genetic mutation—may have been the real catalysts. If a mutation alone explained the emergence of money, we would expect to find monetary behaviors appearing uniformly across all human populations. Instead, they arose only in specific regions under specific pressures.

The more plausible sequence is this: cognitive mutations like hTKTL1 expanded our capacity for abstract thought and social coordination. This allowed larger and more complex societies to emerge, which in turn faced new coordination challenges. Within this context, money evolved as a tool—not as a biological inevitability, but as a response to growing social complexity. Mutation → social complexity → money.

Importantly, money didn’t emerge everywhere. It was independently developed in only a handful of geographically and culturally favorable regions—places with trade routes, population density, and the pressures of surplus and specialization. The concept of money spread through diffusion elsewhere. This rarity underscores that money is not an innate human instinct, but a cultural solution to specific social and economic problems.

Even after the emergence of money, its form has always evolved with society. History does not show a straight refinement toward scarcity—it shows cycles toward and away from scarcity, depending on the prevailing needs of the system.

Today, those needs are changing again. The high-trust, globally integrated world that sustained credit-based fiat money is coming apart. As we enter a more fragmented and uncertain era, societies will once again seek harder, trust-minimized forms of money. This time, the right tool isn’t gold, it’s Bitcoin. Money is evolving once more—not toward growth and expansion, but in response to disintegration and decline. Bitcoin’s unique characteristics make it exceptionally suited for what comes next.

Thanks to Reed, Larry Jr, and Joakim for the proofreading!

Your support is crucial in helping us grow and spread my unique message. Please consider donating via Strike or Cash App or becoming a member today and get more critical insights!

Follow me on X @AnselLindner.

I cannot provide this important Bitcoin and Macro analysis without you.

Bitcoin & Markets is enabled by readers like you!

Hold strong and have a great day,

Ansel

- Were you forwarded this post? You can subscribe here.

- Please SHARE with others who might like it!

- Join our Telegram community

- Also available on Substack.

Disclaimer: The content of Bitcoin & Markets shall not be construed as tax, legal or financial advice. Do you own research.