Common Futurist Fallacies

Technological innovation depends on the underlying growth picture, it's not an independent driver of growth. Demographic decline is the limiter no one sees coming.

I depend on your support of independent content!

Independent Disruption Fallacy

A common mistake in thinking about technology is what I call the Independent Disruption Fallacy, namely the belief that new tools transform the economy on their own, simply by being new and promising productivity gains. In this view, the health of the broader economy doesn’t matter; technology is expected to generate growth by itself.

History shows otherwise. Economic growth does not spring from the tool itself but from its integration into the broader architecture. Markets, institutions, and incentives shape how technology develops and spreads. That is why communist states consistently lag their capitalist rivals in this very area, and why many developing nations struggle to adopt advanced technologies despite their availability. Technological adoption is the product of system-level forces, not the tool alone.

When disruption is treated as independent, stagnation gets reinterpreted as demand for innovation. But in a low-growth economy, adoption can only come through replacement rather than layering — and disruption requires layering. Job-loss fears capture this mistake well: every major technology has come with warnings of mass unemployment, yet each wave ultimately created more jobs than it destroyed, while most existing jobs survived.

Disruptive innovation coincides with an expanding web of activity. Without growth, new technology cannot, by itself, stimulate the economy.

Artificial intelligence is the latest test case. The story goes that AI will make labor obsolete and erase scarcity. But real disruptive innovation doesn’t eliminate what came before — it builds on it. New technology adds complexity.

Old Technologies Rarely Die

History consistently shows that old technologies do not disappear to disruptive advancements.

- Painting and Photography: Portraiture didn’t vanish with the camera. It remained a luxury art form, while photography exploded. Today, there is an order of magnitude more portrait painters in the world than when photography was invented in 1827.

- Theater, Film, and Television: Each medium found its niche, creating overlapping ecosystems. Today, the total number of theater goers is massively more than prior to the other mediums.

- Radio, Records, and Streaming: None killed the others; instead, each multiplied how people consume music.

- Energy: Coal didn’t replace wood, oil didn’t replace coal, and nuclear didn’t replace fossil fuels. Demand grew so fast that all sources expanded.

- Transportation: Horses decreased in number as cars became widespread, but did not vanish. Bicycles are booming globally alongside cars, planes, and trains.

- Printing: Gutenberg’s press was feared as the end of handwriting, oral storytelling, and religious authority. Instead, books multiplied exponentially while handwriting became more widespread with education. Even in the digital age, print books remain robust. Print books expanded from 648 million units sold in 2004 prior to e-books, to 789 million units sold in 2022.

- Hand Weaving and Mechanized Mills: The spinning jenny and power loom didn’t erase hand weaving. They multiplied textile output, expanded the global cotton trade, and birthed whole new industries — fashion, retail, advertising, dyeing. Hand weaving remains massive in absolute terms today: India alone counts millions of active weavers, and artisanal weaving thrives worldwide in cultural and craft contexts.

The Pattern

These examples reveal a consistent pattern: disruptive technologies layer complexity on top of what came before rather than replacing it outright. Old technologies may shrink in relative share, but in absolute terms they often grow. True disruption, like what is promised by AI, therefore requires expansion through added complexity, not the wholesale replacement of existing systems.

Every instance of disruptive technology expands the pie. The Independent Disruption Fallacy assumes growth is irrelevant — that if you build it, demand will follow. But technology does not generate demand on its own; supply does not beget demand. The disruptive potential of technology depends on broader growth conditions, which can be constrained by demographics, debt saturation, institutional decay, ecological shocks, or civilizational decline. Without growth, new technology cannot spread widely enough to be truly disruptive.

I depend on your support of independent content!

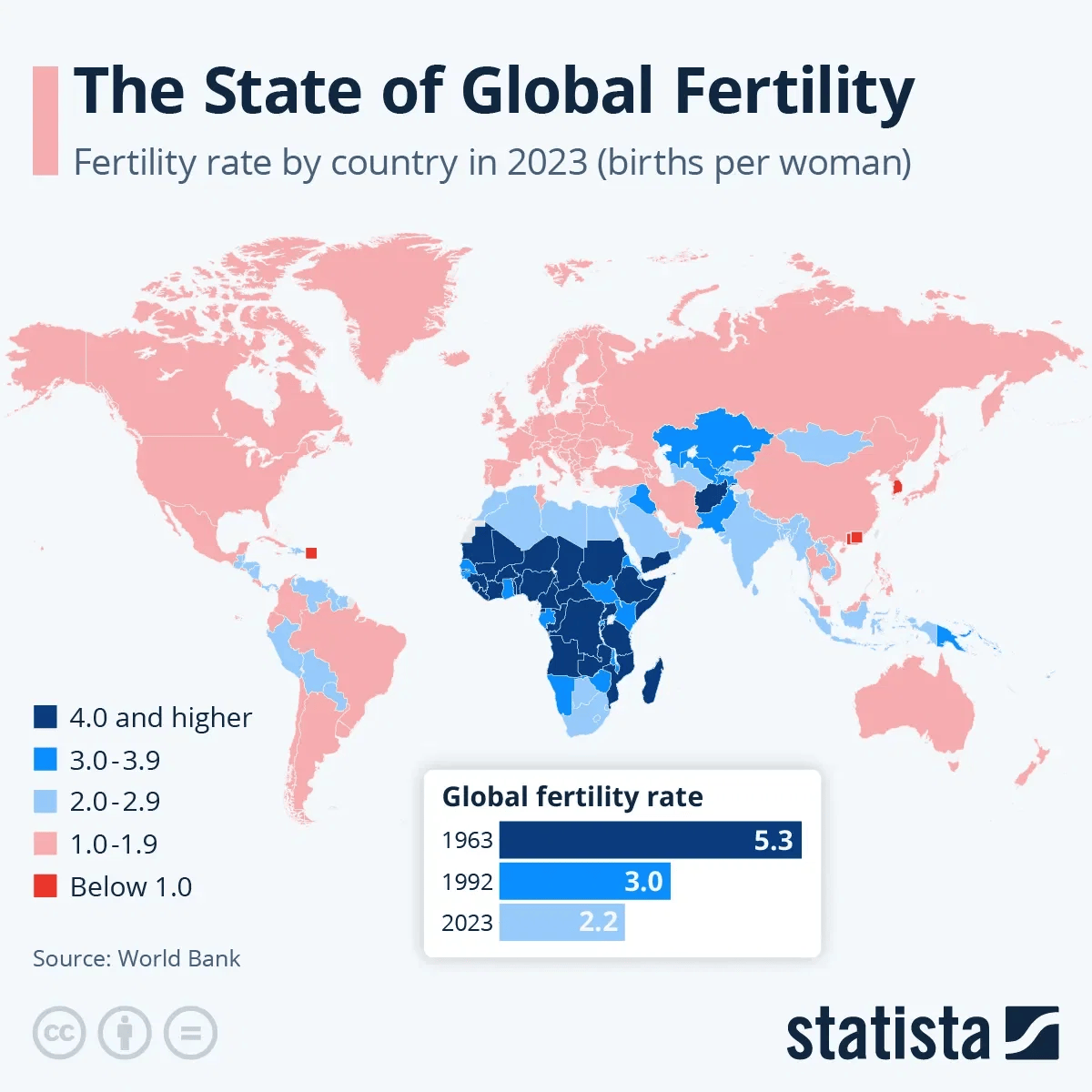

The Fertility Fallacy

The Fertility Fallacy is the mistaken assumption that the economy can continue to grow at the rate it has over the past two centuries despite collapsing fertility rates. It misattributes extraordinary growth, made possible by a unique demographic windfall, to a natural law of progress in technology, governance, or capital.

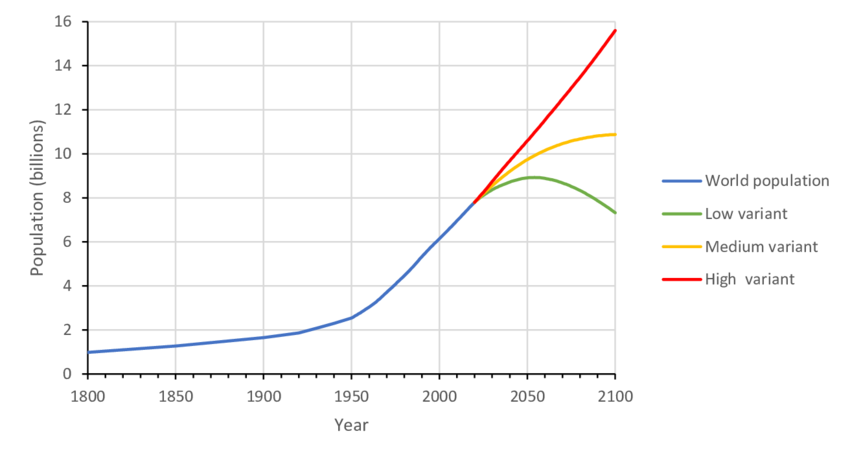

From 1800 to 2025, global population exploded from about 1 billion to over 8 billion. Advances in sanitation, medicine, and nutrition lowered infant mortality, allowing high fertility to translate into an unprecedented surge in population. This “demographic dividend” was not designed or anticipated; it was an accident of history, not a replicable feature of modernity.

Critics might argue that the surge was itself a byproduct of technology, such as better medicine, sanitation, and food production, and therefore growth was really a tech story all along. By this logic, if past technology unlocked economic growth through a population boom, future technology like AI could unlock a new boom of its own.

This objection still falls into the Independent Disruption Fallacy. The infant-mortality breakthroughs that enabled the population surge did not create growth in a vacuum; they built on an existing foundation of agricultural surplus, trade, and early industrial expansion. Without that underlying momentum, the dividend could not have scaled. Pushing the cause back to technology simply shifts the fallacy one step earlier.

Any promised breakthrough that isn’t centered on people doesn’t multiply the economic system in the same way. Humans aren’t just labor inputs; they are demand creators, household formers, and generators of social complexity. They are the subject. A fertility boom automatically broadens the base of the economy in ways no nonhuman breakthrough can. By contrast, machines, energy, or algorithms may increase productivity, but they don’t create demand on their own. They amplify what’s there; they don’t expand the web of actors.

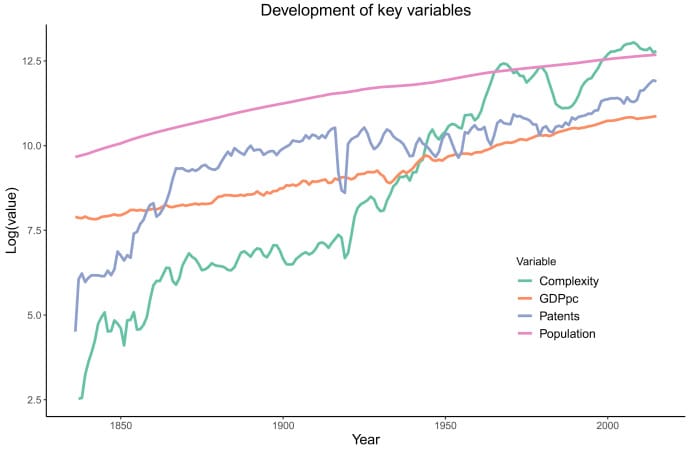

Because this dividend unfolded over generations, it became invisible. We began to assume scaling was the natural state of modern life: more students, more universities, more patents, more startups, more GDP. Growth became the baseline assumption baked into politics, economics, and culture.

Now fertility rates are collapsing worldwide. By the end of the 21st century, many advanced nations will lose half their population. China’s labor force is shrinking, Europe and Japan face rapid aging, and even Latin America and South Asia are below replacement level fertility. This means fewer households, fewer young workers, and fewer consumers. Scaling is no longer guaranteed; we are moving from demographic abundance to demographic drag — smaller workforces, aging populations, and shrinking markets.

The Fertility Fallacy is the error of explaining long-run growth expectations with the same visible factors we use to explain short-term cycles — technology, trade, policy, capital, credit — while assuming a fixed demographic foundation. It's a form of recency bias, just one based on the last 100 years. In reality, all those forces operated through demographics. The rising tide of population made growth look automatic. With fertility collapsing, the tide is going out. Any forecast that projects past growth behavior forward without accounting for demographics is trapped in the Fertility Fallacy.

Growth as a Function of Population

At its core, economic growth can be broken down into two parts: the size of the labor force and the productivity of that labor. GDP growth = Population growth + Productivity growth. Population adds workers and consumers; productivity raises output per worker.

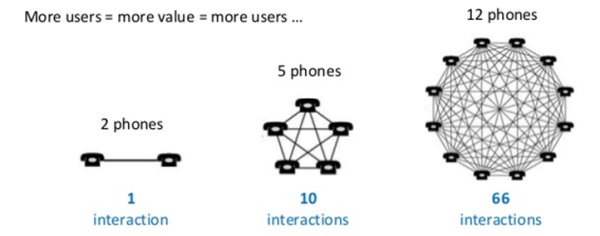

For the last two centuries, these forces reinforced one another. Expanding populations swelled labor and demand, while multiplying the value of productivity gains. A new invention became far more valuable when applied across hundreds of millions of people, creating powerful network effects. Technologies scaled not because they existed in isolation but because each additional person increased the payoff from adoption, innovation, and interaction.

When Population Turns Negative

When population growth turns negative, the cycle reverses. A shrinking workforce cuts output directly and weakens investment incentives. Smaller markets reduce the payoff from disruptive technologies. Aging societies channel resources into pensions and healthcare rather than education and research. Institutions grow brittle and risk-averse. Energy demand stagnates.

The network effects that once magnified growth begin to run in reverse. Fewer people mean fewer connections, fewer markets, and fewer opportunities to share knowledge or spread new ideas. Instead of compounding benefits, negative network effects set in: shrinking demand makes innovation less valuable, adoption slower, and complexity harder to sustain.

Negative population growth does not simply subtract workers; it erodes the very conditions that lift productivity. Disruption stalls, complexity contracts, and the historical feedback loop of growth and innovation breaks down.

Conclusion

The Independent Disruption Fallacy mistakes technology for an autonomous engine of growth. In reality, new tools only transform economies when layered onto a foundation of rising demand and complexity. Without growth, disruption cannot scale.

The Fertility Fallacy assumes that the extraordinary growth of the last two centuries was a permanent feature of modernity, when it was actually the result of a one-time demographic dividend. As fertility collapses, the base of workers and consumers shrinks, and the feedback loop between demographics and productivity runs in reverse.

Taken together, these fallacies explain why technology alone cannot save us from stagnation. AI may enhance productivity, but it cannot create new households, consumers, or social complexity. Without people, there is no disruption.

That is bad news for grand narratives that promise a post-scarcity boom. But it is good news for sound money like bitcoin. Bitcoin doesn't change this story, but it thrives in the specific circumstances of credit-deflation, low or negative growth and and the abandonment of the traditional debt-driven system. Bitcoin is a technology, but it is an iteration on the very old technology of money.

Your support is crucial in helping us grow and spread my unique message. Strike or Cash App or becoming a member today and get more critical insights!

Follow me on X @AnselLindner.

I cannot provide this important Bitcoin and Macro analysis without you.

Hold strong and have a great day,

Ansel

- Were you forwarded this post? subscribe here.

- Please SHARE with others who might like it!

- Join our Telegram community

- Also available on Substack.

Disclaimer: The content of Bitcoin & Markets shall not be construed as tax, legal or financial advice.